How to use LUFS when mastering your track

Following on from our What is LUFS article, it’s time for us to understand the extent to which we need to be mindful of LUFS when mastering music.

But before we can do that, let’s have a quick recap about what mastering is, how it differs from mixing, and why LUFS consideration isn’t completely straightforward.

What is mastering?

Mastering is, as its name suggests, the creation of the final, ‘master’ version of a track.

To understand why mastering is important, consider a modern pop record, whose tracks might have been written by a collection of different producers, recorded in different studios, feature different instrumentation and, in short, sound like a diverse collection of tracks. In order to make them feel like they belong together, a mastering engineer will consider their tone, dynamics, sense of space and stereo width, processing them individually to create a meaningful listening experience all the way through an album of material.

This is just as important if you’re listening to or curating a Playlist on Apple Music or Spotify; you want the flow of music to feel continuous, without huge peaks or troughs in volume or tone, even as you explore diverse musical genres.

Mastering for physical formats

For some formats, there are ‘physical requirements’ for mastering too; specific settings required to ensure accurate, non-distorted playback via vinyl or cassette, which leave some room for judgement of an optimum ‘maximum volume’. In turn, this means that some records sound louder than others.

It was with the arrival of CD that mastering engineers were given a more precise benchmark for what ‘maximum volume’ meant, as suddenly there was a ‘digital threshold’ which couldn’t be exceeded.

Mastering in the age of streaming

But these days, due to streaming services and the way their loudness algorithms work, things are less cut and dried. To understand why, remember that whilst transients are hugely important in music, those peaks aren’t always the best representation of the volume of music overall. Instead, average level readings are a better indicator – measured in different ways, including RMS or LUFS – and they become hugely important when it comes to mastering your music for streaming.

Remember, the detection algorithms at the heart of streaming services want to optimise our listening experience. Among other considerations, they’ll prioritise clarity around the frequency areas where vocals tend to sit in the mix. And they’ll find it easier to do that if there aren’t lots of other instruments competing in those frequencies areas (like guitars, synths or strings etc).

But average level is even more of a significant factor, because none of the online music platforms want to give the impression that any track comes across as louder than any other. And to prevent this, those services analyse average volume across a whole track and make adjustments to any whose average volume is louder than that of others.

The importance of dynamics in your track

Put another way, if your track is loud, all the way through, with a slammed, brickwall approach to mastering from start to finish, those streaming services will detect an overall louder average level and adjust your track down in level, to compensate.

But if your track is more dynamic, either because the levels between peaks fluctuate more, or because there are sections of your track which are appreciably quieter (either a drop section, or a quieter intro, for instance), the louder sections of your track will remain louder.

Remember, you don’t need to print your master at the stated LUFS maximum for Spotify or Apple Music and, in fact, if you do shave 14dB (or the preferred LUFS level each platform uses) off your mixes to attempt to do this, your music will sound a lot less good than other music on those sites. The coding algorithm will take care of overall output level for you, which is why the vast majority of mastering engineers aren’t producing multiple masters of the tracks they work on to meet the needs of CD, TV (for broadcast), vinyl and online streaming services.

Imagine if mastering engineers needed to make versions for every conceivable format in which a track might play; the full mix, the extended mix, the instrumental mix, all multiplied by the number of online and physical formats which that music might feature on – Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube, TV, Film, Radio, vinyl, CD etc – the output requirements would be unmanageable. Instead, mastering engineers are becoming canny as to how to make their masters sound as good as possible across these new formats and, as a by-product, are starting to make more dynamic masters.

Interestingly, song-writers are becoming wise to it too, writing more significant drop sections or deliberately quieter introductions, to ‘game the system’ to ensure that the algorithms at the heart of the streaming platforms don’t drop volume.

Integrated, Short-Term and Momentary LUFS

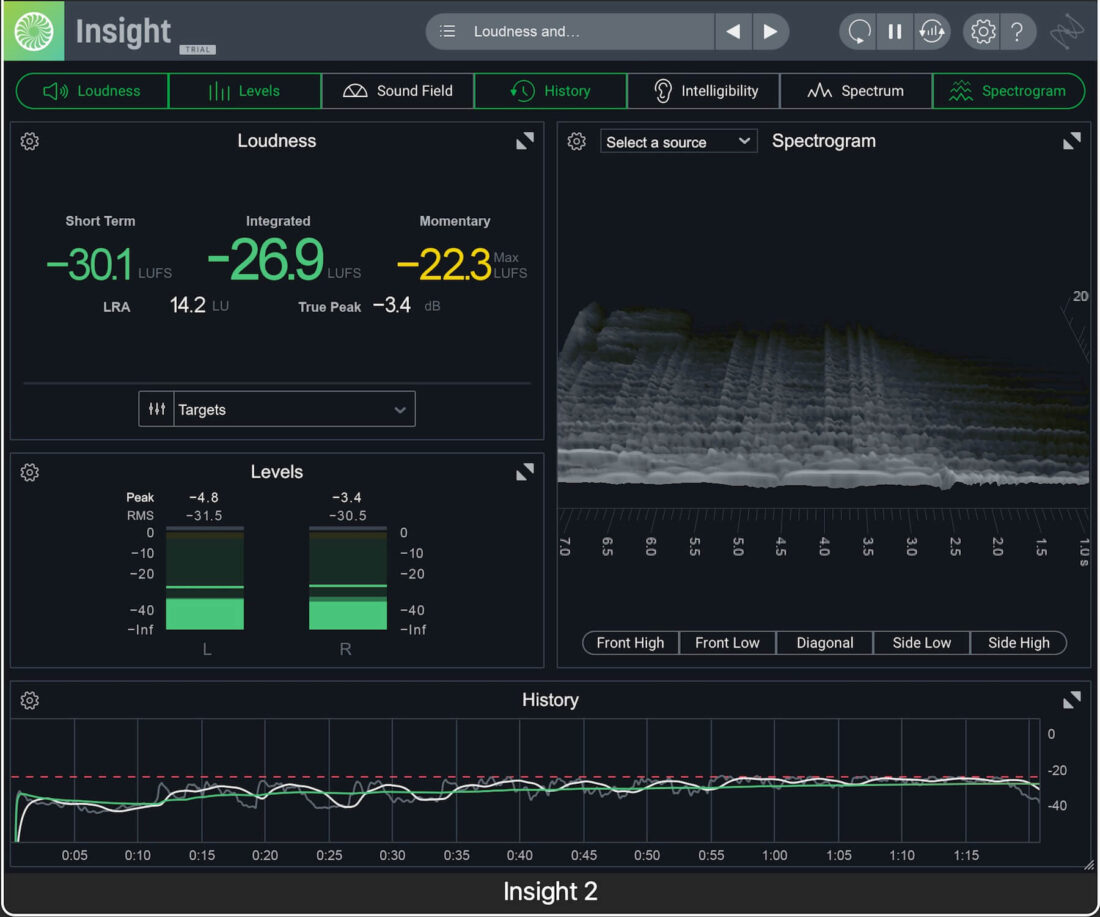

Dedicated meters like iZotope’s Insight will usually break LUFS down into three categories to help you understand levels across your masters.

Integrated LUFS gives you a level measurement across an entire track.

Short-Term LUFS measures the last three seconds of audio, meaning that you can closely monitor how levels change as tracks get louder and quieter, in and out of bigger-sounding sections of your track.

Momentary LUFS allow you to monitor levels across more transient-heavy sections by analysing the most recent 400mS of audio, providing a metering solution which is much closer to peak-level analysis.

In combination, these three readings provide an accurate picture of level across your track and will certainly help you to understand how your tracks might sound on streaming services.