Mixing Bass for All Speaker Sizes

Treat your low frequencies right to help your sound come across on all playback systems – here’s how

Producers might still be sitting in the sweet spot between their two monitors, but the way ordinary people listen to music has changed in spades in recent years. Headphones have always needed to be considered while mixing. But these days, we also need to take bluetooth speakers and even phone speakers into account.

The big problem with smaller speakers – as well as their tiny stereo width – is that they don’t have the grunt to reproduce bass frequencies properly. They simply can’t move the mass of air needed to sustain those big, long wavelengths. There are things we can do to compensate for this, though. The goal is to ensure that our music translates as best it can across as many systems as possible.

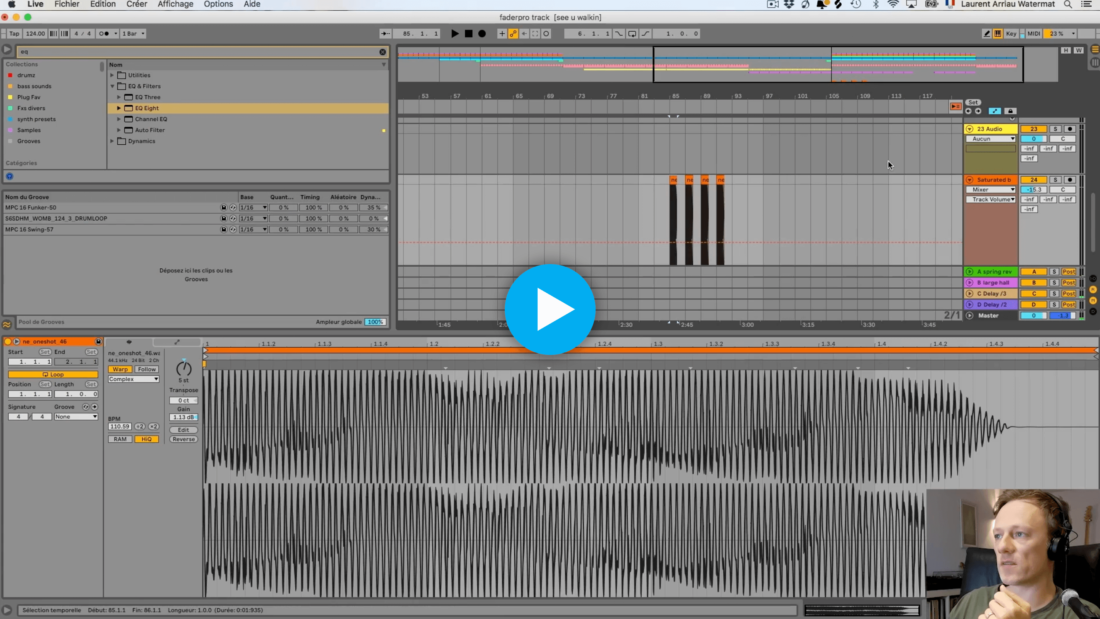

In this video from his Track From Scratch course, Watermat sheds some insight into how he deals with the problem. You can access the rest of this course on its own or as part of a Producers Club membership.

Bass where there’s no bass

Because small speaker systems, such as earbuds lack the capability to produce low-end sound, they can result in missing fundamental frequencies from the overall content of a tone. This means the harmonics of the tone remain, however, the fundamental frequency is missing.

Luckily, our brains are good at filling in missing information, and can allow us to still perceive the missing frequencies based on the harmonic content alone. However, some bass sounds can lack organic harmonic content. This makes it harder for our brains to identify what the fundamental frequencies are.

Thankfully, the modern world of audio engineering, and our current understanding of psychoacoustics, have provided us with solutions to this problem. We can digitally exaggerate, and add to the harmonic content in order to help our brains enjoy the bass that we love so much.

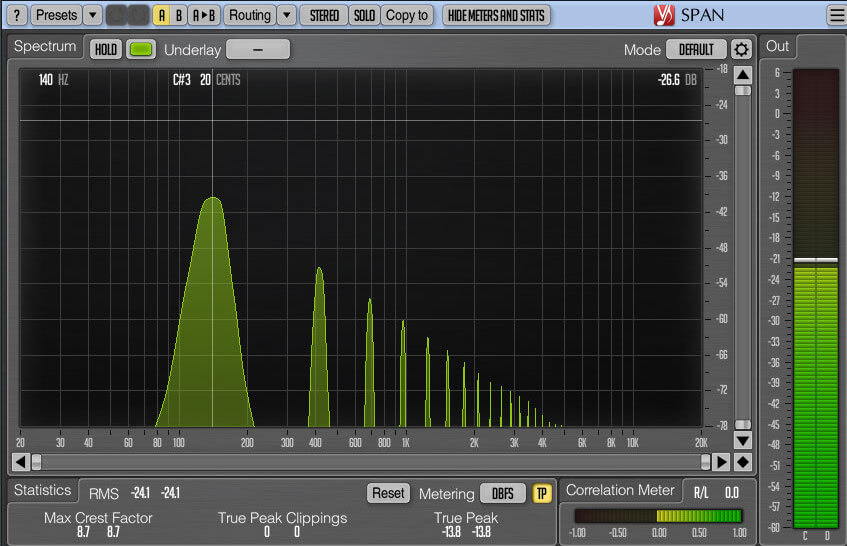

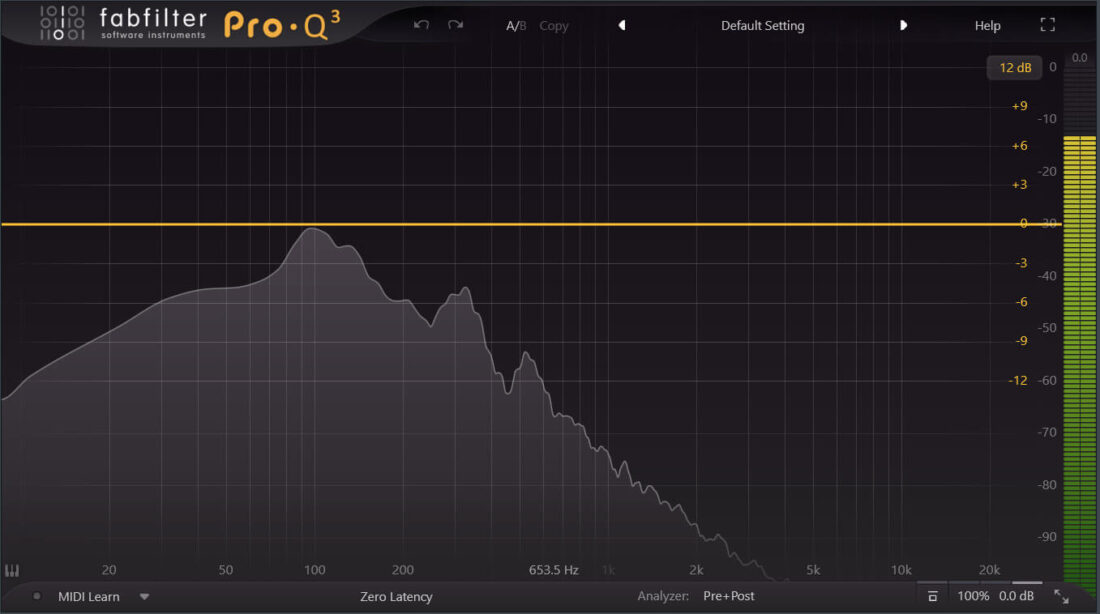

In the image above, you can see the fundamental frequency (140Hz) of this triangle wave signal. You can also see its harmonics, repeating at equal intervals. Because some smaller speaker systems can’t reproduce low-end content, the fundamental frequencies within your mix may get lost when played on some systems.

Saturation and distortion to remedy bass loss

You’re probably aware that saturation plugins work by adding harmonic content to a sound. This additive process is exactly what we can use in order to plump out the harmonics of our low-end. We want to give our listeners’ brains cues to draw from when listening on smaller speaker systems.

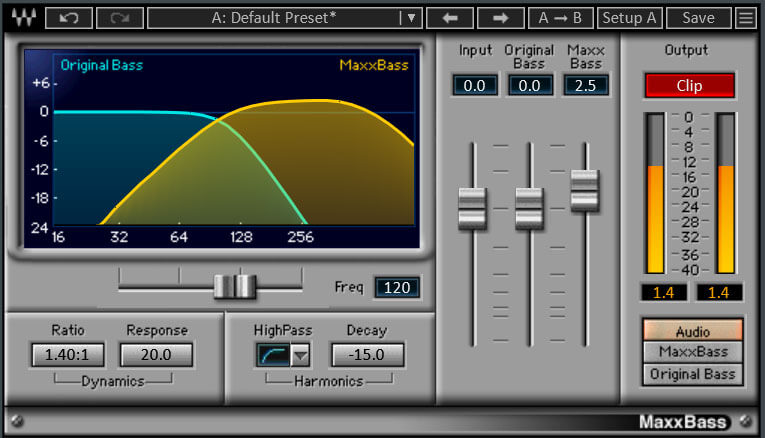

Waves’ MaxxBass plugin was specifically designed to saturate bass sounds and combat the issue of missing fundamentals. Let’s take a look at how we can use MaxxBass, or any saturation plugin, to add some harmonics to a bass track!

Let’s add some harmonics

First, duplicate or buss your bass track so that we can isolate the fundamental frequencies on a replica track. We will use this replica to build the additional harmonics. Later, we’ll mix them with the original track. Once you have your duplicate track, apply a low-pass filter to isolate the fundamental frequencies as fully as possible. In our example below, everything above 200Hz is removed from the duplicate channel. This is a good rough starting point.

Once you’ve isolated your bass fundamental frequencies, you can apply your saturation plugin of choice. You can then adjust the settings of your saturation to your acquired taste.

Remember, the goal is to add a few extra harmonics to the fundamental. DON’T go overboard in this step. If done correctly, your bass will turn from a monotonous weak single band signal, into a plumped-out low-end experience.

During this process, or afterward, you can add a frequency analyser to your effects chain (after the saturation) so that you can see the added harmonics in action.

You can also now blend the new bass duplicate with your original bass track. Or, if that’s sounding a bit too intense, you could solely use the new saturated bass to replace the original. You could even isolate the added harmonics you have created on your new track and then blend that with your original bass. The choice is yours, and there is no one-size-fits-all approach here. Experiment to see what results in the best sounding bass for your track.

Keeping it universal

Because this saturation method is intended to aid your bass when played on small systems, it’s easy to get a bit carried away and beef up the bass to a point where it can ruin your mix on normal systems.

A key thing to keep in mind when saturating your bass with the above-mentioned method is monitoring your mix, and comparing it to similar, relevant reference tracks. Bass is the section of your mix that will sound most notably altered when played on different systems. If you can monitor and test your mix on as many systems as possible, and have a handy reference track to compare it to, you will be able to make a more comfortable final decision on your overall mix.

Monitoring for small systems

The same thinking can be applied when listening to your mix on small sound systems to see your bass saturation in action. It’s safe to say that most producers will be primarily monitoring using professional studio equipment. After all, that gives them the most accurate monitoring when working. However, it is also a good idea to keep some typical lower-quality consumer systems in your workspace. It can be surprisingly helpful to check your mix on those also!

Everyone’s familiar with the concept of the ‘car test’ to see if your mix works. How about the ‘phone test’ or the ‘bluetooth speaker in the kitchen test’. Or if you want to live in 1984, the ‘Alexa Test’. This can be accomplished through Airdrop, Dropbox, Drive, or even rigging up a bluetooth speaker with a line input at your workstation.

If you’re interested in getting your bass up to speed for playback on larger speakers (like the club), check out this article.