What is comping?

Comping is very widely used in the creation of music today. But what exactly is it?

Live music vs recordings

One of the biggest differences between live and recorded music is, of course, that the latter provides us with the opportunity to correct, edit and enhance the music we make. If we’re playing live and hit the wrong chord or forget the lyrics, those ‘errors’ become part of our performance and there’s nothing we can do to fix it. This is why live music is so thrilling – anything can happen and no two performances are ever quite the same.

In the studio, however, ‘mistakes’ can be erased, developed, enhanced, edited, arranged, changed and improved in almost every way imaginable. If we inadvertently play a wrong note over MIDI, we can select it and erase it, or drag it to the note we intended to play. We can use Quantize to get performances in time. If we’re processing audio, we can use Flex Time/Elastic Audio/Warp markers (different names in different DAWs) to pull phrases around to get them in time. And, of course, Auto-Tune and Melodyne are just two examples of plug-ins which allow us to correct the tuning of performances which aren’t pitch-perfect.

Comping – short for ‘compiling’ – is another studio process which allows us to take a performance to the next level. But what exactly does it mean to ‘comp’ a recording?

Comping gives us choices

Comping is an editing technique which lets us to choose between sections of a performance.

Let’s take a lead vocal recording as an example. We’ve got a 1-hour session booked and we want to make sure that we end up with the best possible vocal part by the time the session is over.

Is it likely that the vocalist will nail the best performance on the first take, in one go? That would be perfect – but it’s unlikely.

Even a great first take will frequently prompt some ideas for how a certain section might be performed better. Equally, maybe the vocalist might have underestimated how long a certain note should last or how much breath they’ll need to perform the loudest phrase.

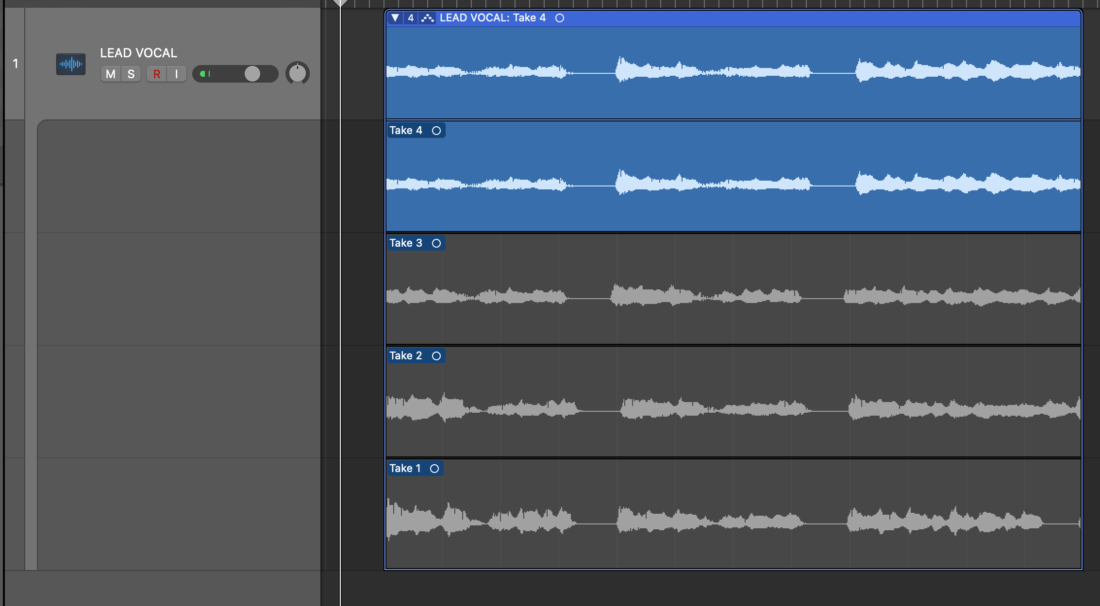

Rather than delete the whole recording in the hope that the next one might be better, producers instead record one after another, ’stacking up’ a series of performances, usually referred to as ‘Takes’. These can either be recorded onto sequential tracks in your DAW – one after another – or onto the same track, into a folder of performances, one on top of the next.

At the end of the session, you’ll have a set of parts, either of the whole song or, more likely, with each verse and chorus broken up into shorter chunks, ready to be mined for the best bits from one phrase to the next.

Comping to produce the best performance

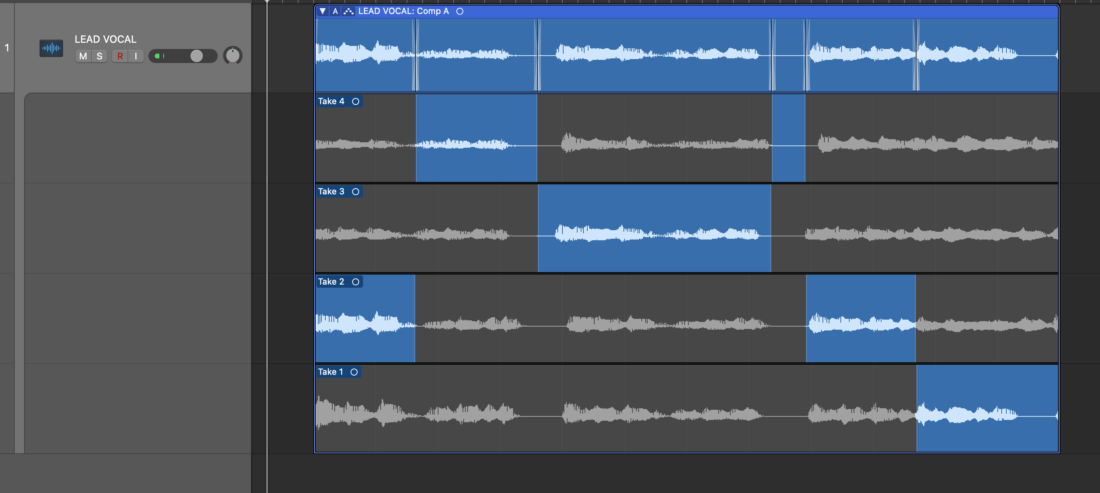

Staying with the example above, comping is the process of turning all of that raw material into the best-sounding vocal performance.

The audio regions you select can be as long or short as you like; sometimes a singer will perfect a series of phrases in one go before the need to switch to a different Take.

Other times, Comps might move between Takes a few times per word, with producers listening carefully to tone, pitch and strength of performance at a much more interventionist level.

Of course, the best possible sounding Comp doesn’t sound like a Comp at all; it sounds like a coherent performance where the ‘joins’ from one section of audio seamlessly give way to the next with no obvious changes in tone or character.

Comping: how to do it

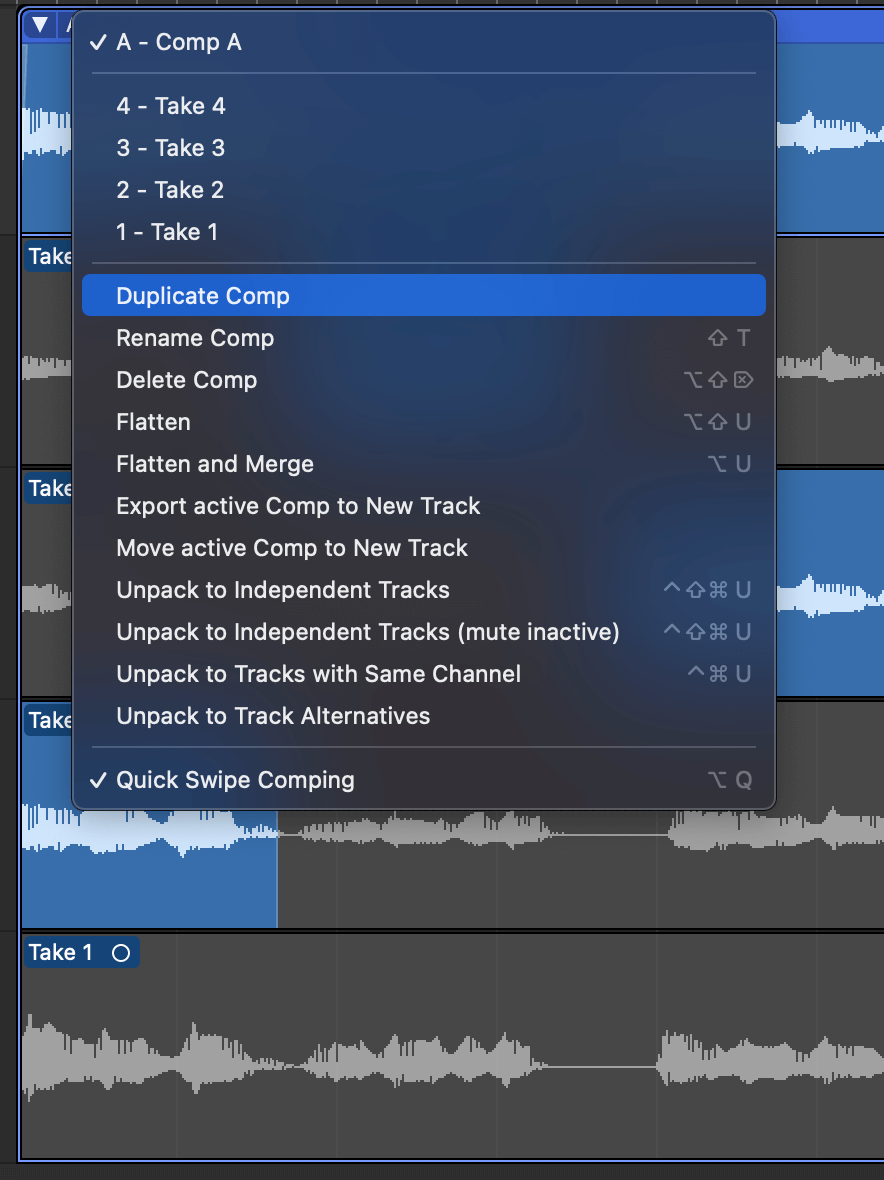

Exactly how Comping is carried out varies from one DAW to another.

Many DAWs now allow you to record Takes one of top of the next on the same track and then provide a rapid-fire way to select between them, dragging or swiping over sections you want to include, prioritising these over redundant, less good alternatives.

The old-school way remains available too, which is to record to multiple, independent tracks and to use the Mute tool to select and de-select regions.

Once a Comp is finished – compiled, in other words – it is ‘promoted’ to the top position on the track, with cross-fading between audio regions (to prevent clicking) usually carried out automatically by your DAW, with those fade lengths fully customisable if you want to smooth out a specific transition.

Often, Comping tools offer options for what you might want to do when you’re finished. You might want to ‘Flatten’ a performance, to reject all of the parts of Takes you no longer need, or automatically ‘Merge’ the selected pieces into a new ‘master’ audio file.

Comping isn’t just for vocals

Comping isn’t limited to vocal parts. Editing across audio of all kinds can benefit from this approach to selecting the strongest parts of a performance.

Audio recorded in multiple lanes (such as a multitrack drum recording) can often be grouped, so that Comping doesn’t have to involve painstakingly selecting your chosen parts from several tracks individually. Instead, a swipe or key command to select a particular section of a Comp is then applied to all tracks, as one.

Selecting Takes and turning them into a part sourced from the strongest sections of multiple recordings is commonplace and, done well, can often lead to a larger-than-life performance.

Remember, you want to create the illusion that the end result is, or could be, a single Take. So Comping nearly always works best when each Take has been recorded by the same singer into the same microphone, channel strip and audio interface, on the same day, in the same session, rather than trying to mix and match between performances captured under different circumstances.

Having produced your Comp, you may well choose to process the end result with tuning plug-ins, or adjust timing. You’ll still need all of the plug-ins you’d usually reach for too, such as EQ, Compression and other processing tools.

But what a good Comp will give you is a seamless performance capturing the very best of your singer or instrumentalist – moment by moment – to produce a great foundation to take on through the mix stage.

What’s next?

If you want to learn more about recording and editing vocals in particular, you should check out Jason Herd’s Recording Vocals course as well as our Studio Short lesson Editing Vocals w/ Eddie Thoneick